THE HISTORY OF THE LIMBURG COAL FIELD

under construction

more information soon

Before 1900 only some scientists showed interest in the underground of the Campine area of the province of Limburg. Geologists and engineers, as the brothers Castiau (1806) and Prof. Guillaume Lambert (1876) put forwards the idea of a second connection between the Ruhr- and the Central English coalfields, following the northern flank of the Wales-Brabant massif.

An explanation for the late discovery of coal in Limburg lays in geological and economic reasons.

In Limburg coal seams nowhere crop out at the surface, and they are burried under a shelf of more than 45 meters.

But at that time, Belgian economy had no need for new and higher coal production and industrialists nor Belgian authorities showed no interest for test-borings. Until the end of the 19th century the traditional Walloon coalfields were able to meet the needs of the Belgian coal consumption.

At the end of the 19th c. Walloon coal production stagnated, coal prices increased, while industry - especially the steel industry - demanded more and more coal. In the years before the First World War more than one third of industry coal had to be imported from abroad.

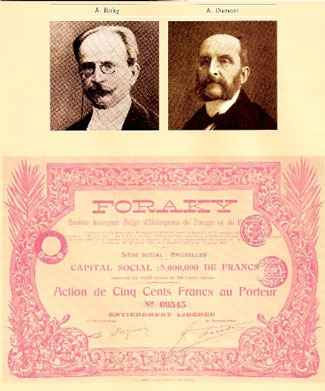

A young engineer of the University of Leuven, André Dumont (1847-1920, former student and successor of Guillaume Lambert) succeeded to set up an exploration company, the 'Société de Recherche et d'Exploitation'.

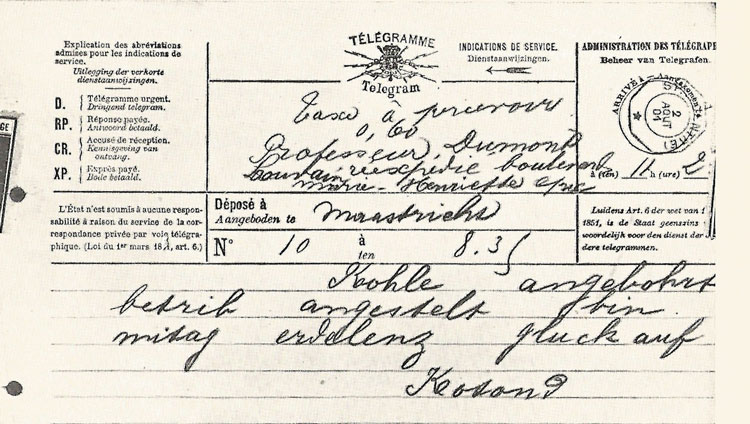

While test drillings of some Liège mining companies stayed without result, the 'Nouvelle Société de Recherche et d'Exploitation' started again in the village of As. In the night of 1 to 2 August 1901, the master driller Koton reached the first Limburg coal at a depth of 541 m. Koton hurried to Maastricht and sent via Leuven a telegram to Dumont who was with his family on holiday in Spa. The telegram was sent at 11 am on 2 August. Koton wrote: "Kohle angebohrt - betrib angestelt - bin mitag Erkelenz - gluck auf - Koton".

|

The result was a coal-rush to LImburg, by the tradional 'coal-barons' and steel-producers, including German, French and Luxemburg capitalists. In 1903 already 60 test drillings were carried out, and some 30 demands for mining concessions were introduced. From this monopoly, and the experiences they acquired in Limburg, a - now disappeared worldwide drilling company ' Foraky, Société Anonyme de forage et de fonçage ' originated (1906), André Dumont being the first chairman of its board. The company disappeared at the end of the past century. |

|

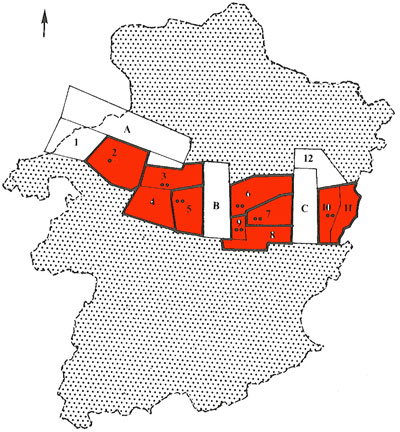

A drill proving the existence of coal was necessary to apply for a concession. On the map: the concessions in red |

|

First coal was only mined a decennium later.

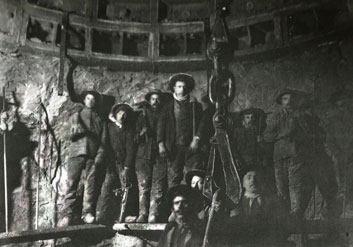

The acqeous shelf and its qicksand layers under heavy pressure caused serious problems. Shaft sinking was only made possible by freezing the soil, a method never used before for shafts of 6 m. diameter, nor till a depth of more than 600 meters. Works had to be carried out at freezing temperatures! In almost every shaft problems occurred, as flooding and mud breaking through. The mine of Zolder has the record of problems as shaft sinking there took 23 years...

|

|

Coal exploitation only went slowly under way.

It was not before the 1930s - when one takes the crisis years into consideration - that the full production was reached in six of the seven collieries. The production in the Houthalen colliery only started in 1939.

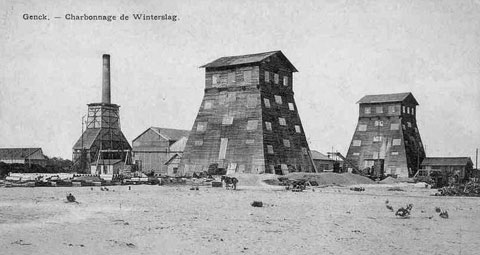

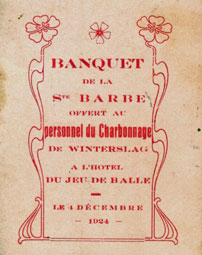

The colliery of Winterslag, sunk in an area without underground quicksand layers, reached the coal seams on July 28th 1914. A couple of days later, on August 4th, the German army invaded Belgium. War of course slowed down the construction, and in most mines who only had started the digging of the shafts had to suspend the works, parts of the equipment were confiscated and moved to Germany. Only Winterslag, where coal seams had been reached and thus was considered to have a strategic value, could continue the works. In 1917 first coal was brought to the surface. After the war the mine was accused of collaboration with the German occupation army.

After the Armistice, most of the before the War undertaken work had to be done over again (e.g. the freezing of the shelf), which urged huge increases of the capital stock. This resulted in a much stronger and dominating control by large abd also foreign capital groups.

Only in 1922 production could start in a second colliery, in Beringen, followed by

- Eisden, colliery 'Limburg Maas' (1922-1923)

- Waterschei, colliery 'André Dumont (1924)

- Zwartberg, colliery 'John Cockerill' (1925)

- Helchteren-Zolder (1930)

- Houthalen (1939)

|

|

Until the Second War the role of the Limburg collieries was limited, although in 1922 the output per miner already exeded the Walloon figures. While the Liège basin - because of the sales potentials to the iron and steel, and other industries - couyld stabilise its production at 5,5 million metric tons between 1927 and 1934, the share in the production of the three other Walloon basins declined from 70% to 60%, while the share of the Limburg basin increased from 6,8% tot 21%.

De devaluation of the Belgian Frank (1935) and the economic recovery after the Great Crisis, together with the increasing threat of a war (1939) and its impact on the iron and steel industry, strenthened the trend. In 1939 Belgium produced almost 30,000,000 metric tons of coal, of which 7,200,00 tons came to the surface in Limburg.Post-war reconstruction needed coal. The miners were called 'the first citizensr of the country' and a 'Battle for Coal' was launched. But despite all propaganda and offering high wages and all kind of social benefits, it was difficult to engage experienced miners.

During the war a lot of people - much more than really needed - went working in the collieries to escape deportation and forced labour in German industries. Notwithstanding the high number of 'miners' during those years, coal production sharply dropped to reach its lowest point in 1944 (13,500,000 metric tons).

|

poster © AMSAB - Institute for Social History, Ghent,

|

Post-war reconstruction needed coal. The miners were called 'the first citizensr of the country' and a 'Battle for Coal' was launched. But despite all propaganda and offering high wages and all kind of social benefits, it was difficult to engage experienced miners.Because of it huge investements were made to mechanize coal cutting and minework in general. The investments were made possible thanks to the Marshall Funds and government subsidies. It also forced to attract workforce from other countries - Italy, Spain, Hungary, Turkey,... which already from the late 1950's onwards turned the region into one of the most multicultural in Belgium. |

But Belgian coal (with the exception of coal from the Limburg basin) stayed to be the more expensive in Europe because of geological causes. Thus Belgian coal economy became difficult to integrate into the 'European Coal and Steel Community'

|

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was first proposed by French foreign minister Robert Schuman on 9 May 1950 as a way to prevent further war between France and Germany. |

The temporary boom in the coal economy, and the effect of government subsidies, led to a maximum production as never was known before. 30,300,000 metric tons in 1952. Even in the outdated and unremunerative Walloon collieries large investments were made.

In 1957-1958, at the beginning of the international coal crisis, Belgian coal sector was weaker than ever before. The Walloon coal sector was dismantled in a quickened pace under the guardianship of the ECSC, and in Limburg the mines of Zwartberg and Houthalen also had to close down, respectively in 1964 and 1966.

As a result of the re-organisation of coal production on a national level, a national company n.v. Kempense Steenkoolmijnen (the 'Campine Mining Company') was established, in which the five remaining Limburg collieries amalgamated. But the old mining companies that were established at the beginning of the 20th century, in fact only sold the money-loosing coalworking to the new company, while the Government promised to guarantee and cover the loses. Meanwhile all land properties, as the buildings and the house in the mining villages, infrastructures, power stations, etc. - the still profit making properties - were kept in ownershiop by the old private groups.

|

|

The heavy strikes of 1970, followed by the fuel crisis, caused a postponement of further closing-downs by Government, but only for a while.

When the Belgian government in the eighties finally closed the subsidy for the five remaining Limburg mines, more than 18,000 miners still worked, including many young people. A manager was appointed who, with a considerable financial envelope, would reduce the remaining mining activity and at the same time provide the region with new economic prospects. The miners, who regularly held campaigns and demonstrations against the plans, were seduced with high incentive premiums and very favorable pension schemes. Miners from the eastern mining basin were once again handily played against their western colleagues. Partly because of that policy the mines in Belgian Limburg could close quite quickly.

The mines in Waterschei, Winterslag and Eisden were closed in 1987 and the western mine in Beringen did not follow much later. As a result, a lot of money remained in the envelope, which after a lot of political tug-of-war and various scandals and scandals, some new projects could be put on the Limburg rails. The coal mine of Zolder was closed in 1992 as the last Belgian mine.

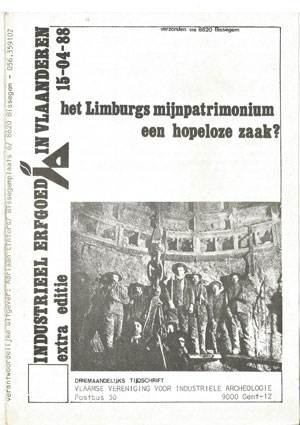

| The slogan the closing-down manager launched was "from black to green", aiming at demolishing as fast as possible all the traces of the mining industry, replacing it by new industries, a large theme park (which never was realised), shopping malls, and some 'natural areas'. Many mining buildings were demolished just after the closing down - as fast as possible. However immediately after the first closures in 1987 requests were launched to save the mining heritage, and when demolishing of some buildings started protest rose against this policy of destruction. Local population, heritage and local history groups, with in the frontline the Vlaamse Vereniging voor Industriële Archeology (Flemish Association for Industrial Archaeology) campaigned to save as much as possible. In april 1988 the association published a special issue of its newsletter, 'The Limburg Mining Heritage: a hopeless cause ?' - this provoked many reactions and reponses as well in press as from citizens and politicians. In a first reaction the then Flemish minister in charge of historic buildings preservation announced that he maybe should/could/would protect one of the pithead gears in each site - as a symbol. This generally was considered by the campaigners 'too little' |

|

|

|

The Beringen Mining Village

The Beringen Mining Village The Winterslag Mining VIllage

The Winterslag Mining VIllage

The reputed Flemish Journal 'Knack', 06-10-1988: No tabula rasa...

The reputed Flemish Journal 'Knack', 06-10-1988: No tabula rasa...